I think that it is important for a rider to be able to maintain her own balance, and that of the horse, independent of the reins. If you can’t do that you don’t have an independent seat, irrespective of how many years you may have ridden!

In a safe, enclosed space, such as an indoor school, ensure a large loop on long reins and try walk, trot and canter and simple transitions. How did you get on?

If it is safe to do so, tie a knot in your reins and drop them completely. Try the transitions and changes of rein. How did you get on?

I tried this experiment with an acquaintance. She couldn’t trust herself to do it. I literally had to go over and pull the reins through her hands. Then she couldn’t influence her horse at all. In her view this meant that “it didn’t work” (not only was there no immediate improvement, things actually got a lot worse). She decided that I was wrong.

What do you think?

When I was first learning about contact it always felt fragile. I’d hold my breath because I didn’t want to disturb it. Then, of course, I lost it. I’d have it on the circle and then my trainer would say “go large”. There would be a rush of anxiety (could I keep it or not). I’d hope and pray I would succeed, then become very fixed and lose it.

What advice would you have given me?

In the 90’s I attended a lecture-demonstration by Anky van Grunsven at Addington Equestrian Centre. Her words still ring in my ears. “Give rein, GIVE rein”. At one point she told the audience that she always feels like there is a little loop in the rein. I think that I understand now what Anky was saying, but for me it is not just the rein we need to give. To give the rein we have to “give” the whole body. You can’t afford to be precious about it. You know when it will be ok because you have the connection in your seat, independent of, and therefore not dependent on, your hand.

It takes a long time to develop a sensitive seat. Riders often use the term “strong seat” or describe a process of “working on their position”. This seems like the wrong choice of words to me. What we want is a sensitive influential seat that connects to the brain directly and is able to release, hold in different muscles for fractions of a second, feel weight distribution and so on.

Seat

What is the seat? Not a trick question as it has been the subject of a lot of controversy between trainers. My definition would be those parts of the body in contact with the horse that are weight-bearing. This means that the seat will include your thighs as well as your “bottom”.

The best way to understand how much weight is carried on the thighs is to sit on your horse bareback. Many un-knowledgeable people will tell you that riding bareback is “cruel” to the horse as all your weight is concentrated into your seat bones which then create huge pressure on the horse’s sensitive back structures. Those of us who have done it (and I, for one, rode bareback for many years on my Arab) will tell you that the weight is spread over a broad area with a lot on the thighs.

The concept of the “perfect seat”

This is talked about in many books but how often is it seen? More to the point how often do you feel you are perfect? What does it feel like? People talk about “long” legs; about feeling like a frog; about becoming a clothes peg; feeling as light as a feather. I have felt at times all of these feelings.

I have found the following “seat” recipe works well for me.

In walk – sit centrally in the saddle and allow your weight to sink down into your legs (long legged feeling). Don’t push your weight down; take the leg away from the horse and feel even weight on seat bones, bring the legs back into light contact and release your weight into your seat. Do not collapse. The feeling is more of letting go. Then grow tall through your back by trying to put a gap between each vertebra (without losing weight in the seat) and soften your neck and jaw …then repeat…let go and up. It is a constant process of assessing areas of tension in our body and releasing them. The Alexander Technique is a great help with this (covered in more detail in chapter 8).

We have to be patient with ourselves and wait for it to happen…not trying to make it happen. In this way you use your skeleton to effectively support your weight so that your muscles are free to be released and free of tension. Release your hips to follow the movement – feel the hind legs coming under – left, right, left, right. As the right hind comes under, the right seat bone is carried forwards and down. This is learning to avoid any influence. We are in “listening” mode. Understanding “what is”; the freedom of the steps; the strength of the steps; his willingness to go forwards; his straightness. This is what some call a passive seat.

A good seat is a balanced seat. This means that ideally 50% of your weight is in the left half of your body and 50% in your right half. I say ideally because there is an intrinsic problem. We humans are all one sided and prefer to use one side of our body more than the other. Muscle is heavier than fat so the better muscled side will be heavier. To improve our riding we need to work on becoming more even. You can make a start now. If you are right-handed consciously inhibit holding this book in your right hand and hold it in your left. For a longer term intervention, try Pilates (see chapter 8 for more details).

Let your weight into your legs and feet – not pushing but letting go – feeling the support of the saddle and the horse’s back and letting him carry you…going with the flow of energy……letting it be. Find the way into the movement by releasing and feeling, not by “doing”. And certainly not by actively pushing with the seat. This only makes it more difficult for the horse to move forwards and gives you sore seat-bones. Believe me, I tried it!

Physics tells us that objects with lower centres of gravity are more stable. Generally speaking, wider and shorter makes for more stability; shapes with weight distributed lower down are more stable. This is why double pony trailers tend to be better balanced than single horse ones. The chassis on the trailer also adds to the comfort of the ride. This needs to be stable but not rigid otherwise the horses would bounce around with every slight change in road surface. The “chassis” for our seat is our pelvis and the muscles around it – our “core” muscles!

The same principle applies when we ride. We need to allow our centre of gravity to be as low as possible. A broader, squatter shape is better than a taller narrower one. How can we achieve this? Let the weight down into your lower body and thighs (remember, seat = knee to waist). Breathe in to the back of your ribs; as you breathe out let all your insides sink down whilst maintaining the structure of your bones (ie don’t collapse your spine). Check that your ribs haven’t flared out and they have release them down again. Release in the area where your leg joins on; then stabilise the upper body above this and let the lower leg hang. Feel the support of the stirrups on the ball of your foot. Don’t push your heel down as some trainers might tell you. Just feel the support of the stirrup and let your weight sink down into your heel. Think it down. But do nothing active!

This is not something we do once when we ride. We do it ALL THE TIME. It is a full time job.

Keep an image of a big-bottomed rider in your mind and think how it would feel to be him. Make your rise smaller in rising trot. Feel that your seat is so heavy that you can hardly move out of the saddle in your rise.

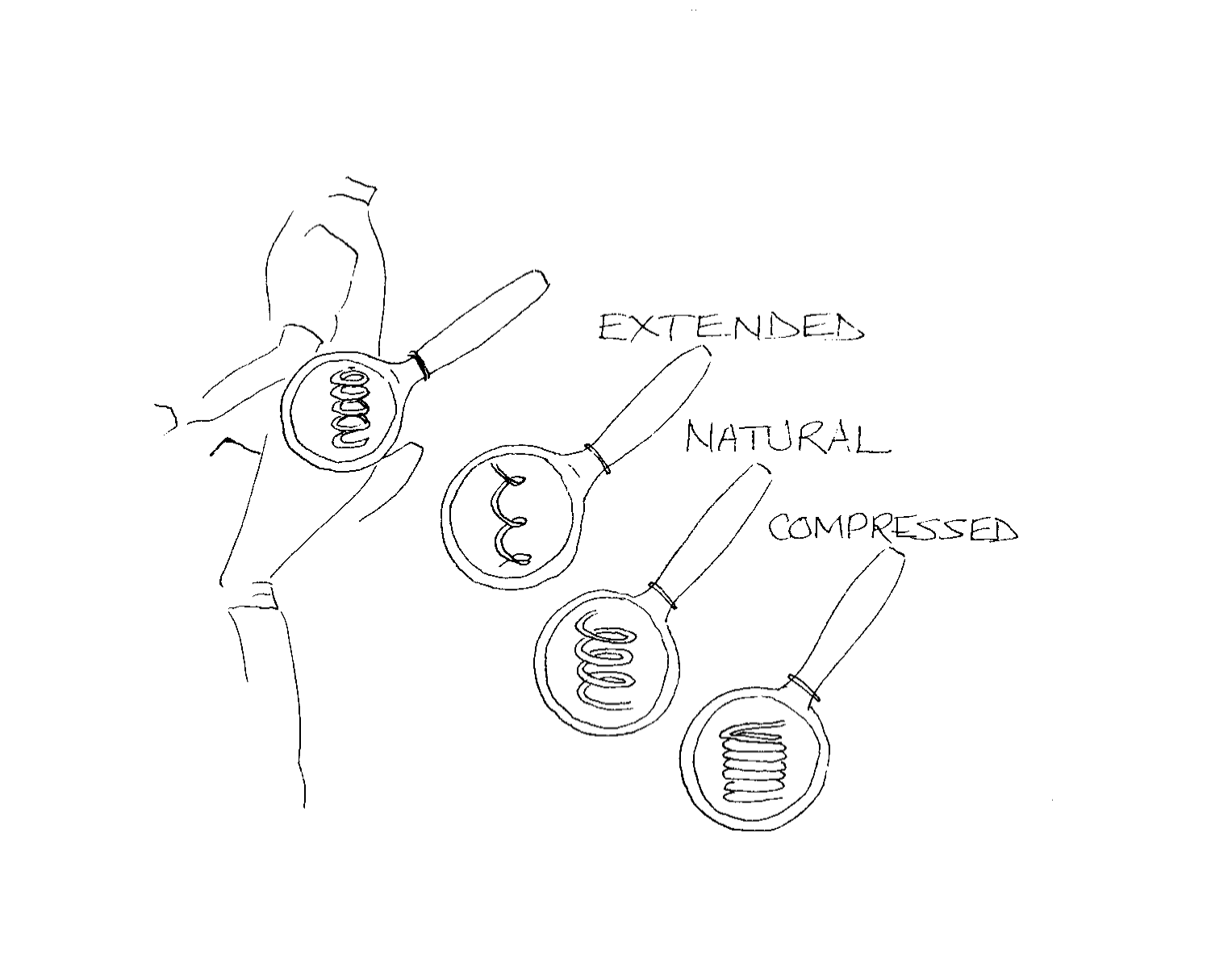

Figure 21 Forces on the rider's body

The shock absorber in the lower back is very important. Think of the small of your back as a thick spring. If we make ourselves too tall we pull the spring and when held there we have no springiness (elasticity). If we collapse our weight down and draw our legs up the spring is totally compressed – again no springiness! The spring can only work well when it is at its natural length and aligned (not bent). This is what body-workers call “pelvic neutral”.

Figure 22 The Spring in the Back

Pelvic neutral allows us to go passively with the horse’s movement. It lets the horse’s energy pass through us without blockage or pushing. As our riding skills improve we can use our pelvis as we would the clutch in a car. Rotating our pelvis back pushes our seatbones forwards and this has a reinforcing (pushing) effect on the horse. Rotating our pelvis forwards pushes our seatbones backwards and this has a holding effect on the horse. It makes it more difficult for him to work through us. We must be careful to keep the energy and never block with the hand when using our pelvis in this way. We can experiment with small changes to our pelvis angle to really understand the power of this tool.

Watch good riders riding. What do you see? Where are they absorbing all that movement? Different riders absorb it in different places. Really good riders absorb it inside. If it is not absorbed inside it will be visible outside. If the seat stays connected but the overall movement is not absorbed then this is when we tend to see nodding heads and wobbly shoulders.

Where do you absorb the movement?