Having a constant conversation with our horse helps maintain attention. This conversation consists of listening, questioning, repeating, explaining, encouraging, reassuring and praising.

We start by listening. On horseback this means understanding how our horse is feeling in his body and his mind. Is he energetic or lazy? Is he stiff or free? Where is he stiff? Do I have his attention or is he spooky? And so on. This enables us to craft questions that help to further diagnose issues, or help to address the issue.

What questions do we ask?

When do we ask?

How do we ask?

How do we respond to his behaviour?

We work on the enablers within our influence – more or less energy, degree of bend, engagement, cadence, length of stride, outline (length of frame), direction (forwards/ backwards/ sideways), degree of difficulty (ie challenge to balance) of movements.

If he is stiff we need to understand why he is stiff. Maybe he has just come out of the stable and needs more time to warm up. Maybe we could have warmed him up more before by turning him out or putting him on a walker or lunging or massage or all of these! If we are sure we have done all we can in this way then we must devise ridden exercises to stretch those stiff muscle groups.

Experiment. Did it help? Why not? What have I learnt? What could I try next?

When to ask?

Timing is of the essence in communicating with our horse. The sequence of each pace and the quality of that pace will dictate the quality of the transition. There are good and bad times to ask for transitions. Good timing increases our likelihood of success. Poor transitions are often the result of bad timing! We riders must understand how the horse moves in each pace, to feel and know when the time is right. For example, the horse strikes off into canter with the outside hind leg. It makes sense, therefore, to ask for the upwards transition as the outside hind is about to leave the ground. To do this we have to feel the sequence of leg movements through our seat. We can also exploit our external circumstances, for example asking for canter as we enter a corner.

How do we ask?

It is not the purpose of this book to talk about aids as they are well covered in other literature, save one point. In French “Aider” means “to help” – so aids are not instructions, they are “helps” – ways of helping or enabling (allowing) our horse. Think - how can I help my horse to understand? What are the choices? What are the likely consequences of each choice? Make your choice and be definite. Follow through to understand whether it worked and if not why not. On and on and on... never ending.

So how can we help our horse to understand us?

I think that the honest answer can be however we want. We can train our horses to our voice, to the clicker, to the leg, to the seat. Whatever we choose. Some of these will be acceptable in competition, others will not. You can have your own private communication system with your horse. It can be that personal.

How does this make you feel? Do you feel excited or threatened at this point?

Inger Bryant (List 1 Dressage Judge) agreed with me on this but said that horses, like humans, can learn multiple languages (communication systems). She works a lot with disabled riders who are unable to aid the horse in conventional terms. She argues that we owe it to our horses’ future to always teach the common language of aids. In this way our horse can be of use to others and so always has the possibility of a new life with others.

William Micklem (5) in his book, “The Complete Horse Riding Manual” also states that “ The difference in aid systems used by different trainers can create problems. A horse that learns to canter from an aid with the outside leg will not understand a canter aid from the inside leg, while a rider’s effectiveness will be reduced if they have to keep changing aids.”

I can see the points Inger and William are making but don’t really understand how this can be achieved. A rider riding a horse for the first time will have to find what degree of aiding is necessary. To the horse each rider will feel different as we are all different shapes and sizes. Personally I don’t believe that there can be a universal language for the horse as we don’t even have a universal language for humans. Not only do we have different base languages, eg English, French etc, we also have different accents and local dialects!

The horse’s response?

The horse can respond in different ways.

The horse says “YES” by doing what we have asked, effortlessly. Brilliant! We reward him by telling him he’ s good, and by not repeating the question.

If he says “NO” by not doing it or by doing it badly then we must think about why. Does he understand what we want? If not have patience – this is learning. See how you can help him out and repeat the exercise. If he does understand check yourself. Ask yourself, is it me? If it is, then correct yourself. If not then it is time to be firmer.

When his efforts please us we reward our horse, reinforcing his positive behaviour, and encouraging him to try harder when we next ask. When the result is less pleasing we must think – what happened and why did it happen? The result of this analysis will enable us to choose the best correction. Often the correction is in ourselves. We monitor the result and then choose to reward, correct or move on to ask another question…and so the conversation continues.

How big a correction should I make?

The answer is to be as soft as you can be and as hard as you need to be.

Sometimes you find yourself lacking in knowledge of options for correction. Better to take time out and research alternative ways forward and implications.

Generally, I think that if there is no physical reason that the horse cannot do as you are asking it is better to make a large and deliberate correction and then give. Ignoring the problem does not make it go away.

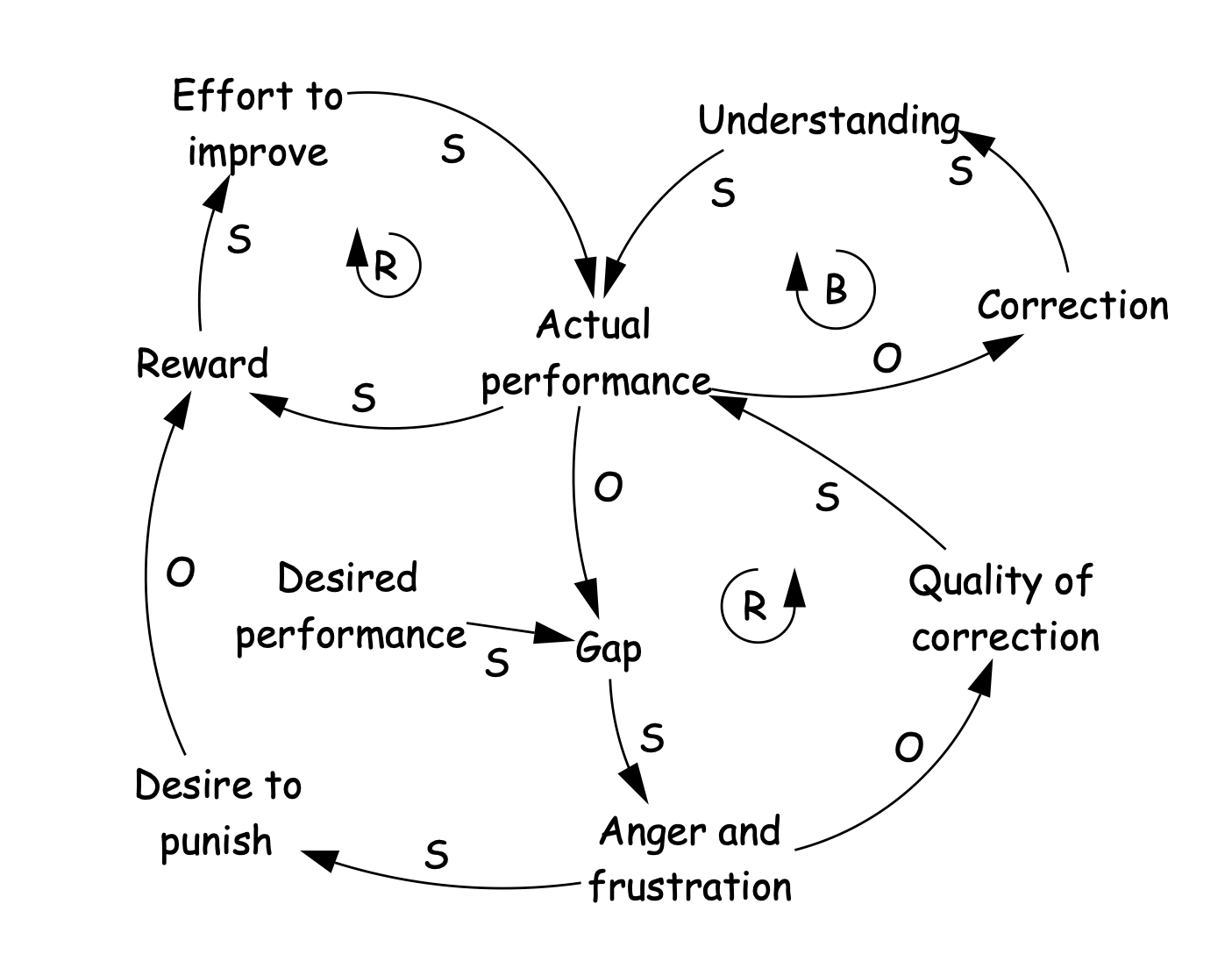

Figure 24 Feedback: Correction and Reward

This process is described in a CLD in figure 24. The better the quality of the performance, the more we reward our horse, the more he tries harder for us and the better the performance. A reinforcing loop. The poorer the quality of the performance, the more we correct our horse, the better he understands what we are asking for and the better the performance.

This requires self control. All too often we are dissatisfied with the gap between what we have and what we aspire to. This can create frustration and anger which can detract from the quality of our correction and create a desire to punish rather than to reward. It is for this reason that the old masters tell us that we must be delighted with small improvements.

For the horse to do what we want he must understand what we want him to do. He must be able to do it. And he must want to do it.

The “understanding” is all about the quality of his previous training and the quality of our current communication.

The “ability to do” is generally physical in nature. Are we unintentionally blocking the movement we have asked for. Is our horse too fatigued?

“Wanting to do” is mental. We can reinforce the horse’s own natural motivation by using reward and anticipation. Like people, though, there are some horses that just can’t be bothered. These horses are best left to riders wanting a challenge!

For each failure in communication we must try to understand why. Only then can we make the most appropriate correction.

Let me illustrate these points with some examples.

Example 1

Eric, my Lusitano, runs through my hand into halt.

Why? Maybe he isn’t listening. Maybe he can’t do it.

Give him the benefit of the doubt, check myself and my preparation, and ask nicely again. Still ignoring me.

Why? He just seems to want to keep going. He is in a world of his own! What should I do next?

Trying the same thing again with no reaction will only enforce his understanding that he can ignore things. So, either I do something else to get his attention eg a small circle before halting, or I use my hand as I ask for halt in the same place, and give immediately.

I reluctantly decide to make a point and use my hand. He is surprised, but halts promptly. I pat him to reassure him he has done the right thing. I repeat the exercise in the same place. He halts immediately. Much praise and do something else.

Example 2

Eric falls out of canter.

Why? He lost his balance!

Why did he lose his balance? I lost my balance and blocked him with my hand! Why did I lose my balance? My weight went too much to the outside on the corner.

Why did that happen? I wasn’t paying attention.

Why? I was bored.

What should I do next? Focus my attention, rebalance myself and ask for the canter again. Reward as soon as I can. Then move onto something else I find less boring.

Example 3

Eric falls out of canter.

Why? He lost his balance!

Why did he lose his balance? He was tired.

Why was he tired? I’d asked for too much without a recovery period.

What should I do next? Regain his attention, rebalance him and ask for the canter again. After a few good strides, back to trot and praise him. Then down to walk. Give him a long rein and leave it there for the day. Make a mental note not to overdo it next time and to be more aware of early signs of fatigue.

Example 4

Eric falls out of canter.

Why? He lost his balance!

Why did he lose his balance? He lost concentration when the cat moved in the corner of the school.

Why? He wasn’t listening to me.

What should I do next? Regain his attention, rebalance him and ask for the canter again. Reward as soon as I can.

Example 5

Eric falls out of canter.

Why? Because I’m a poor rider!

Whilst this may be the case it doesn’t help with our problem does it? A better response would be as for example 1. Try to be specific about what happened – only then can we work on improvement.

So we

Podhajsky in his “Complete Training” (14) uses the terms punishment (as opposed to correction) and reward. For me punishment is a very strong word and should only be reserved for naughtiness rather than lack of effort or inadequate attempts. Punishment and learning do not sit very well together.

I recently visited a yard in the UK. A beautiful young horse was being lunged in the indoor school. Silence except for the rhythmic sheath noise. Many piles of droppings litter the school surface. Round and round in trot and canter. The purpose of the work was to take away the excess energy before he was mounted for the first time.

Each time the trainer approached the horse to change the rein he “attacked” her with his teeth or his front legs. I was shocked. At this point the owner of the yard, and the horse, walked over with a lunge whip and hit the horse. I was shocked. She returned to me and said the horse was a problem and that the only person that could control him was her husband, who hit him with a pipe!

At no point did I see this horse get a reward – only correction or should I say punishment. What I saw was fear. The humans feared the horse and the horse feared them. Each was unable to trust the other.

What would you have done if you were me?

Now imagine the owner asked you for advice. What would it be?

Tension

Muscular tension in the rider can be caused by either mental or physical problems. Low confidence leaves us fearful and tense (literally clinging on with our muscles). The feeling in our mind involuntarily affects our body and leads to hard muscles. In turn this means that the horse is blocked by the rider and is tense also. Muscle tension can also result from injury. The body tenses involuntarily to protect itself. Once again the horse is blocked by the rider and is tense also.

High levels of confidence can bring similar problems. Such self belief can lead to domination (“he will do this”) and force. This can lead to voluntarily tensed and hard muscles. In turn this means that the horse is blocked by the rider. At times I have indulged in this behaviour. “I must make him do this…by now I should be doing this”…but fail to recognise what I or the horse feel like today and that it isn’t going to be possible. This is a recipe for frustration and anger. I’m sure we have all been there.

Can you think of times when you have been too demanding? What happened? Why? What did you learn?

Persistence

When to persist and when to desist? Some coaches believe that persistence is all important. I disagree. I think that the skill is knowing when to persist and when to desist. And this means understanding the system! In that way we don’t walk away when one more try would fix it, and equally we don’t persist in the face of inevitable failure. Persistence which results in self destruction is defeating.