The British Dressage (41) Rules 2006 Appendix 10 states that “The most tried and tested ways of understanding the way of going are the German Scales of Training. These are what the riders in the most successful dressage nation in the world learn in their early years of riding and what the leading international judges talk about at the seminars they give.

Those Scales of Training are:

Rhythm

Suppleness

Contact

Impulsion

Straightness

And eventually, Collection.

Despite the investment in training around the scales I believe that there is still a lot of misunderstanding amongst riders, trainers and judges. One person who responded to my survey offered the following interpretation of the scales:

“…Rhythm must come before relaxation and relaxation before you can establish a correct contact and a correct contact before you can develop impulsion which needs suppleness and elasticity. When these are confirmed you can work on straightness and only then on collection.”

Erik Herbermann reinforces this understanding in his book, The Dressage Formula (4) – “One must have each single requirement before the next step can be attained”.

Can you identify the problem with this logic?

This statement describes riding as a linear progression. It fails to recognise that the concepts are variables and that there are many cause and effect relationships between these variables.

We like to break things down and simplify them but riding is not like that. Complexity is fact. If we fail to understand the complexity and the interrelationships we will fail to improve the performance of the system in a lasting way. We may see an improvement in the short term but in the end we will fail. Moreover, we will also fail to communicate and share our understanding in a meaningful way.

Inger Bryant (List 1 dressage judge) told me “first I aim to have the horse understand what we want and second to develop his physical ability”. I believe this applies equally to riders as horses. But how many training establishments truly integrate theory and practice?

Capturing my client’s business strategies in Systems Thinking (ST) diagrams was a key element of my previous career. It was never easy to do this as few strategies are expressed in the clear, unambiguous style required by ST. It is the same with riding books and other sources of instruction. And without direct access to each author it is difficult to confirm the true intention in all cases.

The official Handbook of the German National Equestrian Federation “The Principles of Riding” (6), does explain the cause and effect inter-relationships between the elements of the scale. Other books on training, notably those by Wolfgang Niggli (29)and Podhajsky (14) also explain their mental models in words. However, in all cases I find it very difficult to grasp “the whole” and there are many unresolved inconsistencies.

Here I will aim to share my understanding of the cause and effect relationships at work and how they affect the horse’s way of going.

Collection

The rider is responsible for training her horse. Her goal is higher levels of collection. But what is this thing we are aiming for? What is collection? How do we know we are achieving it? Until we have understood it we have little chance of achieving it!

The Global Dressage Forum glossary of judging terms 2007 (28) states that “The horse shows collection when he lowers and engages his hindquarters – shortening and narrowing his base of support, resulting in lightness and mobility of the forehand.”

How is this achieved?

Tension is the enemy of collection. This means that we must train our horse to use only the muscles required for the movement, with no excess tension. In this way we develop his core strength and his flexibility. We develop the muscles in his hind quarters to enable him to carry more weight behind which allows him to collect himself and so improves his balance. Higher levels of collection allow us to achieve self carriage which in turn means more lightness.

What is lightness? The term lightness is often used but ambiguous and therefore potentially misleading. Lightness can mean sensitivity or responsiveness. This is about the horse’s reaction to our influence. It may imply that he reacts more quickly and/or to a smaller signal. I prefer to think of this form of lightness as responsiveness. Lightness can also refer to the weight the rider feels in the rein. We have already discussed this form of lightness in chapter 4. Lightness may also be used to describe the horse’s way of going. The quality of the steps can be light, elastic, cadenced and soft; like a ballerina. They can also be heavy, dragging like an elephant. Balance and poise go hand in hand with this form of lightness.

Another school of thought assumes collection to mean “balance”. The implication is that the horse has collection sufficient for a movement when there is no loss of balance. I have some sympathy with this view in that I can see loss of balance is one potential consequence of a lack of sufficient collection. But I don’t believe that they are one and the same thing.

Others believe collection refers to the movement or pace. So, for example, a pirouette is a collected movement and collected trot is a collected pace.

Another point of view is that collection is about the lowering of the quarters achieved by the bending of the joints in the hind legs. It is about redistributing the burden of carrying weight. Theresa Sandin provides an excellent explanation of this aspect of collection on her website (16).

Naturally the horse carries more weight on his forehand. This makes his movement less mechanically efficient. So we train him to carry more of the weight behind. This lightens the forehand, enhances the freedom of the paces and places more weight under the “engine”. To develop the strength necessary to do this takes many years of correct training. I think that what is being described here is the attainment of a very high level of collection.

Have you ever watched a horse approaching and preparing to jump a fence of decent height? To jump well the horse has to adjust himself to bring his weight back over his pushing hind legs at the point of take off. When allowed the freedom, the horse collects himself naturally in preparation for the task in hand. The same happens in a downwards transition. The horse will look to lift his head, neck and back as he does this. The rider must allow this to happen with her body.

I believe that posture and balance don’t define collection. Rather they are symptoms of collection having been achieved. The term collection comes from the French verb “rassembler” which literally means to collect. But this begs a question. What is it that we are collecting?

Baucher, another eminent French ecuyer, believed that he was “collecting the forces of the horse in his centre in order to ease his extremities… The animal finds himself transformed into a kind of balance of which the rider is the centre-piece…The rider will know that his horse is completely gathered when he feels him ready as it were to rise from all four of his legs.” (31).

Figure 27 The Rechargeable Battery

From my own experience I believe that I am collecting energy. I think of my horse with a huge rechargeable battery in his quarters. When I ride him in certain ways I collect energy in that battery. I recharge the battery and hold it there for future use.

Movements which create more energy then they expend are “collecting” movements. They include: work in confined areas; small circles; tighter turns; lateral work; downwards transitions; rein-back; counter-canter; approaching a fence; slower paces. The assumption here is that all the work is correctly executed. Incorrectly executed work achieves nothing.

This stored energy can be released from the battery intentionally to create powerful extensions. Movements which expend more energy then they create are “releasing” movements. They include: work in open spaces; straight lines/diagonals; faster paces; extended paces; landing from a jump.

Energy can also be released unintentionally through leakage – usually, as with all batteries, through faulty connections. In the rider’s case the connections allowing leakage are our seat and hands. Too weak a contact will leak energy. Too strong will block our ability to release energy.

Energy can also be wasted when we are not straight and streamlined. For efficiency we need the part in front of the engine to be aligned with it. We can also waste energy when we go too fast. Pushing our horse forwards faster and faster is inefficient movement.

Have you felt this yourself? Correct extensions use energy that we have already accumulated. The feeling is that it is always possible. We simply allow it to happen. It looks effortless, and it is. In contrast incorrect extensions are fuelled on energy created in the movement – it looks full of effort, and it is. As Paul Belasik says in his book, Dressage for the 21st Century (7), “If nothing can be let out, nothing was being stored up”.

The battery, essentially the horse’s physique, grows stronger through training and so more able to create and contain larger amounts of energy.

So, just to summarise on collection. I believe that riding is about efficient movement. Movement requires energy. An effective rider generates energy; conserves it well; and uses it efficiently. She manages the horse’s battery!

To ensure this energy is used efficiently it should not be blocked; it must flow freely through his body. So tension has an impact on impulsion. To avoid wasting energy we need our horse’s body to be mechanically efficient. The term we use in dressage is straightness.

Straightness

The BD Rules Book 2006 states that “The aim is that the hind legs step into the tracks of the forelegs both on a straight line and on a circle, and that the rider has an even feel in his reins.”

I think a better term for “straightness” would be “alignment”. We often talk about straightness for the horse but it is very important for the rider too. Why is it important? It is important for efficiency; to achieve ease of movement. This is the effect in the short term. But there is a longer term need for straightness. Better alignment gives us more even wear and tear on the limbs. It helps to maintain soundness and therefore our horse’s ability to sustain his performance in the longer term.

Can true straightness ever be achieved? Straightness is an ideal. It should be possible for a horse with perfect conformation but how many of those do we see? However, it can always be improved. How? To improve alignment we have to “decontract”; to remove excess tension. But this is chicken and egg because to let go we must be aligned – otherwise we will lose balance.

The horse must allow us to direct his available energy by accepting our contact; in the hand; the leg and the seat. For him to accept we must be acceptable. We must make ourselves as easy to carry as we possibly can by improving our own position (aligning ourselves and removing tension to the minimum necessary) and continuously softening ourselves to ensure we don’t block him, anywhere.

Impulsion affects balance. Too much or too little can result in lost straightness and/or lost balance.

Our ability to straighten our horse is affected by the horse’s conformation or his natural degree of straightness. And the degree to which he will allow us to do this.

We have already seen that tension (what’s happening on the inside) affects straightness (what we see on the outside). One sign of straightness is tracking true. In other words, the hind prints follow in the same arc as the fore prints. Tension in the horse affects tension in the rider. A horse with a tense back is not easy to sit to!

What affects tension? Calmness in the mind and relaxation affect tension. Tension affects balance and therefore regularity. In turn, attending to the rhythm and keeping things the same is comforting for the horse. It calms him and reduces tension. He starts to breathe more deeply and regularly. One outward sign is relaxed snorting. Easier work, well within his capabilities, is also calming for the horse.

So far we have discussed the rider’s impact from the point of view of her seat and balance and therefore her ability to impede her horse. We have also mentioned the rider’s impact through training, fittening and feeding. An effective rider trains her horse to become responsive to smaller requests. If she is unable to do this she has to resort to force and physical strength. The more the rider uses force the more tense the horse will be, the less able he will be to move freely forwards and so the harder the rider will have to work. Good riding appears effortless for horse and rider because it is effortless. You do have a choice.

I have felt the effect of the variables and relationships both for myself and for my horse.

Take some time to consider how they have worked for you.

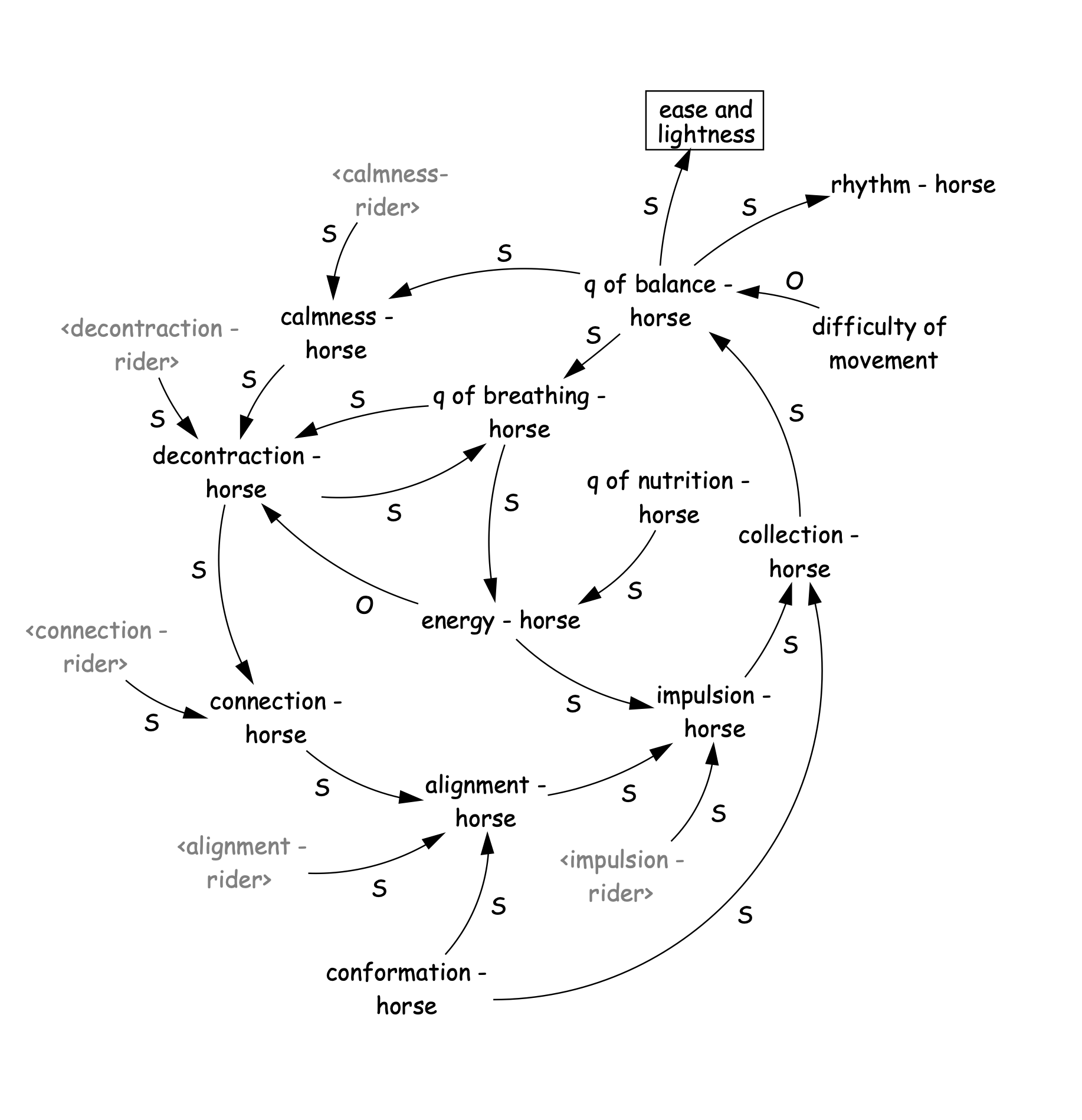

We can combine all these variables and relationships into a causal loop diagram shown in Figures 28 (horse) and 29 (rider). The diagram was created in a software package called Vensim (36). Variables which have been copied and appear elsewhere in a larger diagram are shown in grey in angled brackets thus: “<xxx>”.

Starting on the right hand side with collection -The greater the degree of collection of our horse, the better his balance will be and the more he will move with ease and lightness. He will be able to maintain his balance and rhythm through increasingly difficult movements. Indeed, Inger Bryant explained that the test of whether the horse has sufficient collection in a dressage test is whether he can maintain his balance and rhythm for the movement in question.

Collection is affected by impulsion which is in turn affected by energy and alignment (straightness, mechanical efficiency). The horse’s alignment is affected by the rider’s alignment; the degree to which the horse allows the rider to influence him through the connection, and of course, his own conformation.

Figure 28 Scales of Training Inter-Relationships (Horse)

The quality (q) of the connection is affected by the decontraction of the horse and the quality of the rider’s connection to him. I think that this is what we call “feel”.

The horse’s decontraction is affected by his breathing, his calmness, his energy level and the decontraction of the rider. The better the quality of breathing the more decontraction; the greater the decontraction the better the quality of breathing. Energy needs to be balanced with calmness. All other things equal more energy gives less relaxation. This is the great rider challenge; managing energy and maintaining decontraction. To improve decontraction, the rider must decontract herself and/or reduce energy levels. John Micklem always told me – never create more energy than you can control. This has implications for feeding too.

Calmness is the foundation on which everything else is built. Like us, when our horse feels challenged, shown physically by a loss of balance, he will tend to lose his calmness. As he becomes more able to maintain his balance in more and more difficult situations so his calmness will improve too. The rider has a major influence here. She must be calm herself and she must aim to manage her horse’s calmness by working on the boundary of his comfort zone.

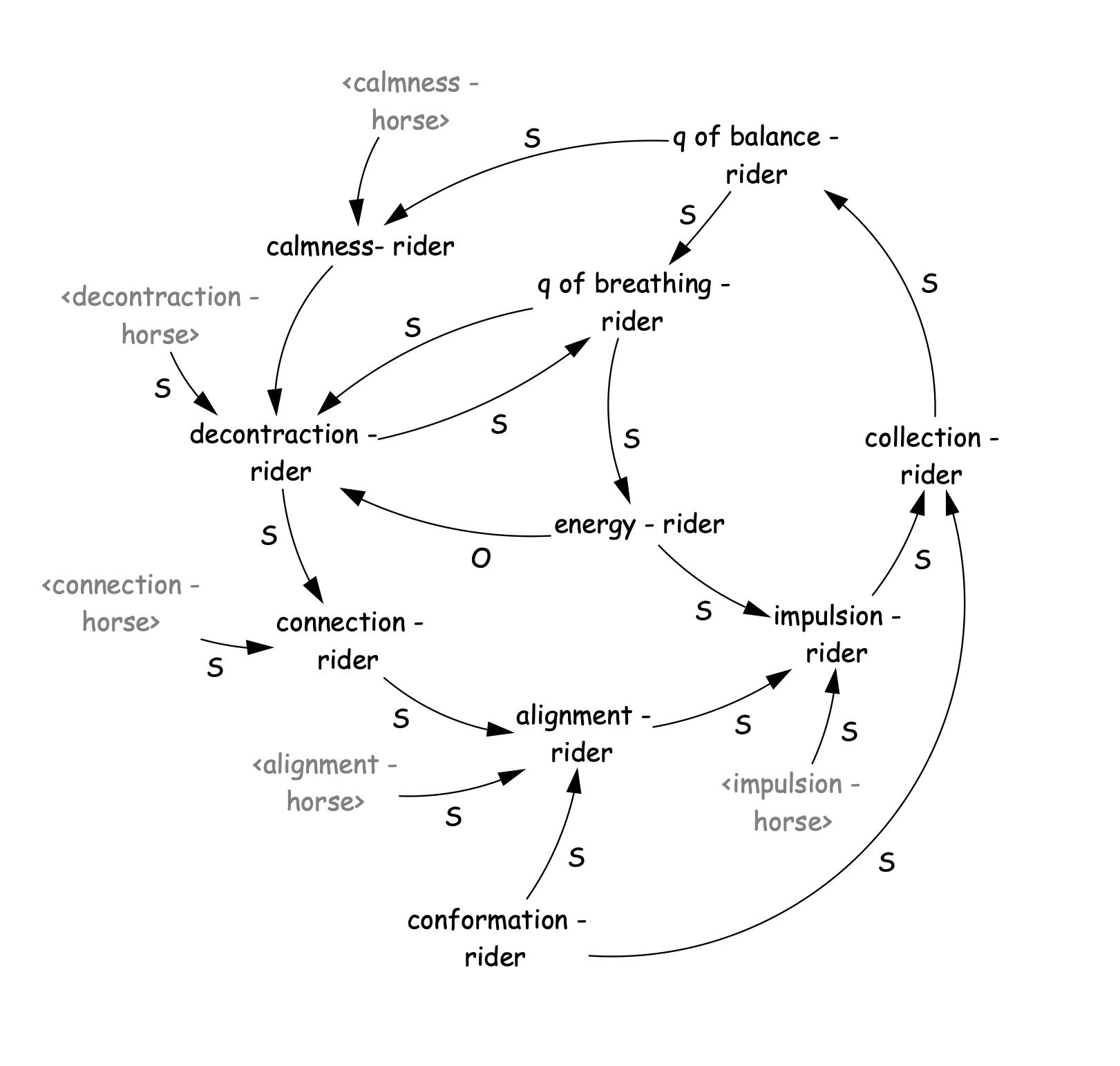

The same relationships are at work for the rider.

Figure 29 Scales of Training Inter-Relationships (Rider)

Can you describe the relationships in Figure 29? Have you experienced these relationships at work when you ride? How does what you have experienced differ?